Introduction

Throughout my academic and professional career, I have been involved in a wide variety of project types in a wide variety of geographic settings. I have also cultivated a strong personal interest in transportation issues, particularly in regards to rail transit. I have volunteered at the Illinois Railway Museum outside of Chicago and assisted with the operation and restoration of historic streetcars and rapid transit railcars. Here in Cincinnati, I have lent my assistance toward the efforts to build a streetcar system linking downtown and Over-the-Rhine.

As an aspiring architect, my favorite design typologies are those that involve structures that related in some way to rail transit; where the means of conveyance is integral to architecture and becomes part of the built environment and functions as a gateway to whatever locale is being served, be it a major urban passenger terminal or a small train station in the hinterland. The train station, rather than merely a place where one catches a train, serves as a civic gateway and commercial hub. Nowhere is that more true than the case of New York’s Pennsylvania Station.

Problem Statement

To the lament of architects and preservationists in New York and throughout the world, McKim, Mead, and White’s grand Pennsylvania Station was demolished in 1963 and replaced with a rat maze of underground concourses and tunnels buried under a new Madison Square Garden and a drab office tower. Today, the station is cramped and overcrowded, chopped into disparate dzones for each of the three railroads that serve it (Amtrak for regional and long-distance trains, and Long Island Rail Road and New Jersey Transit for commuter trains). Perhaps just as importantly, any sense of “arrival” in the nation’s largest city that was evoked with the original structure has long since been replaced with the dread of navigating one’s way through cramped, stuffy passageways and a gauntlet of panhandlers.

Momentum is building for the construction of a new and expanded facility, but a debate has emerged between many in the city’s architectural community in local transit advocates and planners. Some architects see an opportunity for an iconic structure that pushes the avant garde of design, while many planners and transit advocates favor a more utilitarian approach with a strong emphasis on expanded capacity.

This debate represents a false choice between formalism and utilitarianism, and ignores the experiences of arrival and departure from the point of view travelers and others who use the station.

Literature Review

Somewhat surprisingly, Jane Jacobs makes only passing references to passenger rail transit in her epic tome The Death and Life of Great American Cities. A disciple of Jacobs, William H. Whyte, goes into further detail in his book City: Rediscovering the Center, praising the virtues of newer light rail transit in cities like Sacramento and bemoaning the loss of the original Pennsylvania Station.1 Whyte, in comparing various urban design conditions, holds up Grand Central Terminal as the far superior passenger experience than the new Penn Station, and one would be hard-pressed to find a soul who disagrees. Jacobs and Whyte, however, were writing about urban conditions in general, and not specifically about rail transit and railway stations. For that, it is necessary to turn to some lesser-known authors with more specialized expertise on this particular building type.

Carroll Meeks provides a thorough architectural survey of Western railroad stations built since the Industrial Revolution in his 1956 book The Railroad Station: An Architectural History. Meeks notes that with the development of passenger rail travel in the 19th century, there was no historical or functional precedent for facilities to serve this new mode of transportation and thus, it had to be invented.2 Meeks then outlines the development of the railway station over the next century, grouping the maturation of this building type into distinct phases: picturesque eclecticism, functional pioneering (1830-1845), standardization (1850s), sophistication (1860-1890), megalomania (1890-1914), and twentieth century style (1914-1956). Ironically, Meeks’s book was published just as passenger rail travel in the United States had begun its long decline in favor of the private automobile.

During the renaissance of British passenger rail travel in the 1990s after a number of years of privatization and disinvestment during Margaret Thatcher’s administration, Brian Edwards published The Modern Station: New Approaches to Railway Architecture. In this book, Edwards describes the role of the modern railway station in broad terms, rather than merely as a place where passengers board and disembark trains. This role includes serving as a center for commerce and movement, a meeting place, an urban gateway, and as a civic icon. Edwards then goes on to describe the challenges and opportunities unique to several station typologies, including the international or mainline station, the airport station, the suburban station, the rural station, the underground station, and the light rail station.

While Edwards takes a look at modern-day railway stations and uses them as examples for future projects, Peter Burman and Michael Stratton reflect on the older stations that are now in need of conservation and restoration in Conserving the Railway Heritage. This book, published at the same time as Edwards, is a collection of essays by various authors that highlight various approaches to conservation and preservation of historical pieces of railroad infrastructure. As with Edwards, the primary focus is on British railways, although Edwards does cite a number of European examples and a smaller number of Asian and American examples.

For a more global focus, the Art Institute of Chicago has published Modern Trains and Splendid Stations: Architecture, Design, and Rail Travel for the Twenty-First Century, a companion to an Art Institute exhibit by the same name from December 2001 to July 2002. Edited by Martha Thorne, this book includes three essays by various authors about the future of passenger rail travel in the United States and in the world at large, followed by examples of new and proposed projects across the globe that point toward that future.

Stakeholders

As with almost any large-scale public infrastructure project, the client (i.e., the entity paying to have it built) is distinct from the end users who utilize the facility on a daily basis. As such, I prefer the term stakeholders as a more inclusive term to describe not only the client(s) who would be formally responsible for building and operating the facility, but also the tenants and general public who encounter the building during their travels and/or who work in the building as employees.

The institutional stakeholders, i.e., the client in a formal sense, would mostly likely be in the form of a joint venture between several of the following entities, in descending order of prominence:

- The City of New York does not currently have a major direct ownership stake at Penn Station, but exerts considerable influence in other ways on behalf of the public. On July 24, 2013, the city made the first major policy decision to begin the process of creating a new Penn Station, by approving an extension of Madison Square Gardenís operating permit to only the year 2023. The city, though its ability to condemn property via eminent domain and revise zoning ordinances, is in a powerful position to guide the fate of Penn Station by aquiring property and providing zoning incentives for adjacent development. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) funds from new development in the area of the station could then be used by the city toward the design and construction of the new station itself.

- The State of New York, through the Empire State Development, is leading the redevelopment of the Farley Post Office building into the new Moynihan Station.

-

Fig. 1.03: Westminster Station on the London Underground’s Jubilee Line extension The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), operator of subway, bus, and commuter rail service in the New York metropolitan area. The MTA operates two commuter railroads: the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) with its primary hub at Penn Station, and Metro-North Commuter Railroad with its primary hub at Grand Central Terminal. The MTA leases and operates Grand Central Terminal, and there are long-term proposals to introduce some Metro-North services to Penn Station via the West Side Line and the Hell Gate Bridge. The MTA also operates six subway lines and several bus routes that directly serve Penn Station. The MTA is a state agency with headquarters in New York City. (This is a result of the city’s fiscal crisis of the 1970s, in which many public services that would normally fall under the purview of the City of New York were ceded to state control in Albany.) The MTA has undertaken several large-scale infrastructure projects in recent years, including the East Side Access project to bring LIRR service to Grand Central Terminal, the Second Avenue Subway project, and the extension of the #7 subway line to Hudson Yards.

- The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, owner and operator of the region’s three major airports, the PATH subway system (which has its 33rd Street terminal a block away from Penn Station at Herald Square), the World Trade Center complex, the Port Authority Bus Terminal on 42nd Street, and all interstate river crossings between New York and New Jersey. Although the Port Authority currently has no major role at Penn Station, they have taken over the redevelopment of the Farley Post Office building into a new concourse and ticketing hall for Amtrak, immediately to the west of Penn Station. The Port Authority would also be the most likely operator of any new express rail service between Penn Station and the three airports. The Port Authority is a quasi-governmental agency created by the states of New York and New Jersey, with its new headquarters under construction at the World Trade Center. Like the MTA, the Port Authority has an extensive portfolio of major capital projects in the region, including the rebuilding of the World Trade Center.

- New Jersey Transit, operator of commuter railroad, bus, and light rail service throughout the state of New Jersey, with Penn Station as its main commuter rail hub. Secondary commuter rail hubs exist at Newark Penn Station and Hoboken Terminal. NJ Transit also contracts with the MTA’s Metro-North Commuter Railroad to operate two commuter rail lines in Rockland County and Orange County in New York State. NJ Transit is a state agency with headquarters in Newark, New Jersey.

- Amtrak, the current owner of Penn Station and operator of the nation’s regional and long-distance rail system. Amtrak is a federal agency, with headquarters in Washington, DC. Penn Station is its busiest hub. Amtrak is in the process of relocating its ticketing, baggage claim, and administrative facilities from Penn Station to the Farley Post Office building across 8th Avenue. (Although branded as Moynihan Station, it remains part of the overall Penn Station complex.) Amtrak is also taking the lead with the proposed Gateway tunnel and expansion of Penn Station.

- The United States Postal Service, as owner of both of the Farley Post Office building and the Morgan Sorting Facility, properties that are key to unlocking the potential of an expanded Penn Station and revived Midtown West neighborhood.

For the purposes of this project, it is presumed that Amtrak would cede ownership and control of Penn Station to either the City, the MTA or the Port Authority, or to a new joint entity that includes representatives of each. Amtrak and NJ Transit would then operate as tenants of the new facility. (A recent precedent for such action can be found in Los Angeles, where Amtrak ceded ownership of that city’s historic Union Station to the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which is now in the process of developing an ambitious master plan for the station and its surrounding precinct.)

In their proposal to the Municipal Art Society, SHoP Architects proposes a Gateway Task Force headed by Vice President Joe Biden, the United States Transportation Secretary, the Governor of New York, and the Mayor of New York City. This could serve as a potential framework for the leadership structure for the redevelopment of Penn Station and the surrounding area. However, it is anticipated that the MTA would most likely be the operator of the new facility once construction is complete.

Commercial stakeholders, private entities with a strong financial interest in the current facility, include:

- The Dolan Family, owners of the Cablevision cable TV service and Madison Square Garden. The creation of a new Penn Station is dependent upon the relocation of Madison Square Garden to one of several nearby sites, and so far the Dolans have resisted efforts to move the Garden. Although the specific location and design of a new Madison Square Garden falls outside the scope of this thesis, it is anticipated that a new Penn Station and relocated Madison Square Garden will ultimately be beneficial to the Dolans.

- Vornado Realty Trust, owner and manager of much of the commercial real estate that surrounds Penn Station, including Two Penn Plaza which currently sits atop Penn Station immediately to the east of Madison Square Garden. Although the redevelopment of Penn Station would require the demolition of Two Penn Plaza, several studies have indicated that the real estate value of Two Penn can easily be recaptured via the redevelopment of several under-utilized parcels into high-rise office space. Vornado also owns One Penn Plaza, a 50-story office tower to the north of Penn Station. The lower levels of this building contain retail spaces and an elevator lobby that open directly into the existing Penn Station.

- The Related Companies, which is part of a joint venture with Vornado to redevelop the Hudson Yards site and the commercial portion of the Farley Post Office building.

In addition to the institutional and commercial stakeholders, there are major cultural stakeholders who may not have a direct financial stake in Penn Station, but who exert considerable influence on behalf of architects, planners, the arts community, and other advocates who champion a livable city with a strong artistic and cultural heritage. These stakeholders include:

-

Fig. 1.04: Norman Foster’s Canary Wharf Station on the Jubilee Line extension The Municipal Art Society of New York (MAS), a nonprofit organization founded in 1893 to fight for “intelligent urban planning, design, and preservation through education, dialogue, and advocacy.”3 The MAS was instrumental in developing New York’s first zoning laws that pioneered restrictions in building heights and setbacks, as well as the creation of the New York City Planning Commission, the Design Commission, and the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The MAS led the efforts to prevent demolition of Grand Central Terminal, Lever House, Radio City Hall, and other icons of New Yorkís architectural heritage.4 More recently, the MAS has been at the forefront in advocating for the relocation of Madison Square Garden and the construction of a new Penn Station.

- The Regional Plan Association (RPA), founded in 1922, is an independent nonprofit planning association focused on improving the quality of life and economic competitiveness of the New York City metropolitan region. According to its mission statement, the RPA “aims to improve the New York metropolitan region’s economic health, environmental stainability and quality of life through research, planning and advocacy.”5 The RPA has had a considerable influence over some of the regionís largest infrastructure projects, and has formed an alliance with the Municipal Art Society in advocating for a new Penn Station.

Not least importantly, there are the end users of Penn Station, the people who pass through the station from Point A to Point B, or who work there. A hypothetical sampling of Penn Stationís end users would include:

- Eddie, an office worker from Nassau County, who takes the Long Island Rail Raod to his job in Lower Manhattan. At Penn Station, Eddie typically grabs a coffee and bagel while making the transfer from the LIRR to the downtown subway.

- Michelle, an undergraduate sociology student at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, who enjoys spending a day in New York once in a while. She also has family in White Plains, New York. To save money, she takes SEPTA from Philadelphia to Trenton, where she transfers to NJ Transit for the ride to Penn Station. To make the side trip up to White Plains, she must take a subway from Penn Station to Times Square, transfer to another subway to Grand Central Terminal, and then take Metro-North.

- Jeremy, a programmer from London who has recently been tapped to work for a tech startup in Brooklyn. From his shared flat in South London, Jeremy will take the Underground to Paddington Station, where he will board a comfortable express train to Heathrow airport. Upon landing at JFK, Jeremy must then board the slow-moving AirTrain to Jamaica, and then wait for a crowded LIRR train to Penn Station. From Penn Station, Jeremy will then take two subway lines to his friendís loft in Bushwick, Brooklyn. Complicating matters is the fact that Jeremy uses a wheelchair due to a car accident during his first year in college, and so much search for a barrier-free way to transfer from one mode of transit to another.

- Simona, a barista at the Starbucks located on the lower concourse level of Penn Station. Jessica works at Starbucks while taking night classes at the Borough of Manhattan Community College downtown, and while she enjoys her job and doesnít mind putting in long hours to accomplish her goals, resents spending nearly her entire work week in a place with no natural light or views to the outside.

- Paul is a retired widower who lives on a fixed income in a subsidized apartment a couple blocks south of Penn Station. Paul has always enjoyed watching trains, and since his wife passed away five years ago, Paul enjoys spending time at Penn Station, watching the hustle and bustle of the crowds, and taking note of the trains that come and go.

- Jessica is a newlywed who lives with her husband in Washington Heights and who works as a human resources manager for Macyís on 34th Street. Although she lives in the city and commutes entirely via subway, Jessica uses Penn Station daily because it’s the closest subway stop to her place of employment. She’ll exist the subway at 8th Avenue when the weather is nice, and walk the two blocks to Macyís outdoors along 34h Street. But during inclement weather, she’ll walk through Penn Station itself, which saves a block of walking in the rain.

These various stakeholders all have differing objectives, ranging from managing the nation’s largest transit agency to simply being able to easily get from one part of town to another. The ones who give any thought about architecture at all are likely to have widely divergent opinions about what good architecture means. It would be safe to assume that, when it comes to a new Penn Station, they are skeptical of having another iconic structure by a “starchitect” that puts the ego of the designer ahead of the needs of the stakeholders and general public. At the same time, they have a strong desire for a new station that is intuitive, light-filled, monumental, and reflecting of hopes and ambitions of the era in which it is built. In addition to meeting the pragmatic needs of effectively getting people from Point A to Point B, the stakeholders want the new Penn Station to be a place that appropriately marks the occasion of arrival in New York City, a place where people want to gather for a drink or meal the way people do at Grand Central Terminal rather than being a place that people want to escape.

MAS Design Challenge

The current incarnation of Penn Station was built at a time when passenger rail travel was in serious decline; the automobile and the airplane were the transport modes of the future. Fortunately, passenger rail transit has undergone a renaissance in recent years, most notably in Western Europe, the United Kingdom, and Japan since the end of the Second World War, but also (to a lesser extent) here in the United States over the past couple decades. With Amtrak setting new records for ridership6 and President Obama’s recent calls for a national high-speed rail network, attention is shifting back toward the possibilities of passenger rail transit. A number of major American cities have put forth their own plans for new and upgraded railway stations, and decades of modern rail-related construction in Europe and Asia provide ample examples for best practices in the case of New York’s Penn Station.

In recent months, the Municipal Art Society of New York, the Regional Plan Association, and New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman have taken up the cause of a new Penn Station. With Madison Square Garden’s operating permit expiring this year, Kimmelman and the MAS have urged the City of New York to approve an extension of the permit for only ten years (as opposed to the indefinite extension sought by the owners of Madison Square Garden), giving the city time to decide on the future of the site.

In the spring of 2013, the Municipal Art Society invited four prominent New York firms to re-envision Penn Station and the surrounding district. SOM, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, SHoP Architects, and H3 Hardy Collaboration each took a holistic, “big picture” look at Penn Station, Madison Square Garden, and the surrounding neighborhood and proposed schemes in response that ranged from the fanciful to the more pragmatic.

Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill

Of the four schemes, SOM’s arguably took the most formalistic approach, with a grand gesture in the form of a large, circular orb-like structure suspended above the site by four skyscrapers acting as table legs. The ground plane was occupied by a large park above the station proper, with a central oculus providing some daylight to the concourses and platforms. Madison Square Garden is shown to be occupying the two city blocks immediately to the south of the Farley Post Office. While a portion of one of those blocks is likely to be demolished as part of the new Gateway project, the remainder is mostly low-rise residential. The idea of displacing hundreds of residents for a new sports arena, especially while much more suitable sites are located nearby, is dubious at best. At the regional level, SOM proposed direct rail service between Penn Station and to the region’s three major airports, which is an idea worth implementing regardless of the fate of Penn Station itself.

At the human scale, though, the SOM scheme begins to break down. While it’s hard to argue against the idea of more public parks, the idea of a large city park under a giant orb supported by four skyscrapers would seem to be one of those ideas that looks much better as a computer-generated rendering than as actual built architecture. In reality, the park (which occupies five entire city blocks — two more than Penn Station and the Gateway project’s Penn South expansion combined) would likely be under a permanent shadow, and bring to mind the worst of 1960s-era urban renewal schemes that involved large-scale demolition of entire urban neighborhoods.

Worse still, SOM glosses over the capacity, circulation issues, and the passenger experience of the station itself. While their renderings show sleek Japanese-style bullet trains instead of boxy-looking American commuter trains, the platforms and concourses remain mostly cut off from natural daylight, and would likely be only modestly improved over the current conditions. In essence, SOM replaces Madison Square Garden and Two Penn Plaza with a park and some additional high-rises, but apparently does little to improve the station itself.

Diller Scofidio + Renfro

DS+R, in contrast, has a much greater focus on the passenger experience, exploring the activities in which people are engaged while waiting for a train, and proposing additional program elements to respond to those needs. They also delve into contemporary notions of monumentality and the issue of an integrated facility rather than the current balkanized layout of Penn Station, and propose relocating Madison Square Garden to within the shell of the western half of the Farley building, an idea that came close to actual implementation within the past few years. Also addressed is the confusing way in which train information is conveyed to passengers. These are all valid ideas that need to be part of any conversation about the future of Penn Station.

However, the proposed scheme by DS+R, a birds-nest of intersecting ramps and corridors that contain various program elements, doesn’t seem to address these questions as effectively as it could. Capacity issues are not addressed, and the two-block footprint of their scheme doesnít take into account the planned expansion of Penn Station a block south as part of the Gateway project. Also not addressed are the need for clear, self-evident circulation and passenger facilities. While visually compelling, the proposed scheme would seem to be at least as confusing and counterintuitive as the current facility.

H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture

In contrast to SOM and DS+R, H3 Hardy approached the design brief with more of a focus on transportation connections and urban design, rather than purely as an architectural project. Their scheme proposes extending the 7 subway from Hudson Yards to Penn Station, bringing some Metro-North trains into the station via the West Side Line through Hudson Yards, relocating Madison Square Garden to the Hudson River waterfront adjacent to the Jacob Javits Center, and using the western half of the Farley building for educational purposes. While moving Madison Square Garden to the riverfront may place it out of easy reach to transit riders (a proposed LIRR station at Hudson Yards notwithstanding), the other ideas are worth exploring as part of any rebuilding of Penn Station. Moving the Borough of Manhattan Community College to the Farley building would also free up the BMCC’s current site in Lower Manhattan for large-scale commercial development, which could be factored into the financial equation for a new Penn Station.

With this in mind, H3 Hardy’s scheme for the station itself and the immediate precinct seems to be more of an afterthought. Like the other schemes, there seems to be relatively little focus on the passenger experience, and like the SOM and DS+R scheme, the H3 Hardy scheme for a new Penn Station comes with the obligatory rooftop park.

SHoP Architects

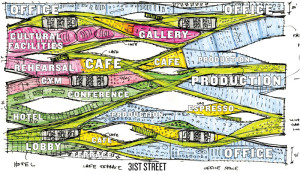

The Gotham Gateway scheme by SHoP Architects was a refreshing change of pace from the other three schemes for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, the passenger experience was given heavy consideration, and theirs was the only scheme to show clear, logical circulation pathways from the platforms to the street level. SHoP’s proposed station includes a variety of retail and amenity spaces that one would expect at a major train station, and the main waiting hall itself is shown to have a light, airy feel that would be a most welcome improvement over the current underground labyrinth; the scheme was the only one to show the potential of a grand space in which arrival takes place.

SHoP’s Gotham Gateway scheme was also unique in that it was the only scheme to go into detail about some of the more logistical and pragmatic issues that will need to be resolved if Penn Station is renewed: security concerns, energy efficiency, natural daylight, service access, and probably most importantly, the funding and policy mechanisms that would need to be implemented in order to see the scheme to fruition.

Critiques that could be raised in response to the Gotham Gateway scheme include the fact that the Gateway Park would involve the demolition of a city block that includes a high percentage of residential units; the northern half of the block is mainly commercial and will likely need to be demolished as part of Amtrak’s Gateway project, but it’s hard to think of a compelling reason to demolish the southern residential half. SHoP’s proposal to ban trucks from the immediate vicinity of the station for security purposes probably isn’t realistic, and the required security checkpoints to enforce such a ban, along with the excessive sidewalk setbacks, risks turning the site into another demilitarized zone similar to the new World Trade Center site a couple miles to the south. Regarding the station building itself, SHoP proposes dividing the passenger facilities into three zones (one for each of the tenant railroads) that would lessen but not entirely mitigate current facility’s balkanized organization. How long until New Jersey Transit, for example, decides to renovate their third of the station into something that’s visually and functionally incompatible with the other two-thirds?

That said, these are relatively minor critiques, and it was decided to use SHoP’s Gotham Gateway scheme as the starting point for further development.

Response

The MAS Design Challenge, of course, generated considerable coverage within the architectural press as well as local news outlets. Coverage was generally favorable, but a handful of prominent transit advocates — particularly those of a more libertarian bent — saw the exercise as another “vanity project” that serves as a means for politicians to spend vast sums of taxpayer money to build a monument to themselves at the expense of more basic improvements to transit service.

Benjamin Kabak of the Second Avenue Sagas blog wrote the following:

The latest vanity project that’s come to view is this plan to replace Madison Square Garden with a grand new Penn Station. Few New Yorkers would dispute the charge that Penn is a dump. It is clearly in need of some work, and MSGís place atop the station will forever interfere with improvements. Relocating the arena and rebuilding the train station makes sense if the money makes sense. How much should we spend on a majestic building when rail needs — such as a new trans-Hudson train tunnel — are so glaringly obviously more important? 7

This response and the ones like it ignore a number of important realities. The passenger experience within the space of the station, while easily dismissed as mere “aesthetics” or window dressing, is at least as important as more concrete factors like the number of trains per hour when it comes to transit planning and design. The success of the Washington Metro is due in large part to the functional yet elegant design by Harry Weese Associates, to the point where the Metro has become a tourist attraction and icon of the city in its own right (while costing less to build than the more traditional subway stations the transit agency had originally envisioned, it should be noted). Whether we choose to acknowledge it or not, the design of our physical environment has a profound impact on our well-being as individuals and collectively as a society. Yes, we should be responsible with taxpayer money, but there comes a point when frugality becomes counterproductive. It’s not enough to accept a substandard design for such an important part of the city and then tell our grandchildren, “Sorry, that was the best we could do. It’s your problem now.” That was the approach taken with the second Penn Station in 1963, and repeating that mistake is simply not an option.

On a more fundamental level, the need for a new Penn Station and the need for increased rail transit capacity into Manhattan are not mutually-exclusive. In fact, one cannot happen without the other. Expanding capacity at Penn Station without a major rebuild of the entire facility is physically impossible, and improving the passenger experience at Penn Station without addressing crucial capacity issues would be akin to putting perfume on a pig. These problems are joined at the hip, and cannot be solved in isolation from one another.

On July 24, 2013, New York’s City Council followed the urging of Kimmelman and the MAS and approved the 10-year extension, effectively beginning the countdown for the relocation of Madison Square Garden. As of 2014, newly-elected Mayor Bill de Blasio and a majority of City Council are on record as having expressed support for relocating Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station. With that hurdle cleared, the stakeholders can now focus on implementing a longer-term strategy regarding the future of Penn Station.

Summary

The available literature and precedents point to a multitude of examples where a historic railway station has been modernized to serve as an urban gateway and meet the needs of modern-day travelers, and other examples where railway stations have been created from scratch in locations that previously had no access to rail transit at all. Despite a wide variety of locations and specific program requirements, what the most notable examples have in common is the ability of the modern railway station not only to serve the purely pragmatic function of providing a place where the traveler can board a train (Penn Station already provides that, barely), but also to serve as a portal to the city in a way that no other transportation facility can match. Unlike airports, train stations are located in the heart of the urban core. Unlike a freeway exit or parking lot, train stations bring people together and serve as civic icons and nodes for commercial activity. Transforming New York’s Penn Station into a similar urban gateway and multi-modal transit hub isn’t without significant challenges, but prior examples and the MAS Design Challenge have demonstrated that these challenges can be overcome in an effective manner.

Illustration Credits

All illustrations by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Fig. 1.05: SHoP Architects, Gotham Gateway Presentation to the Municipal Art Society, May 2013

Fig. 1.06: Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, Presentation to the Municipal Art Society, May 2013

Fig. 1.07: Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Presentation to the Municipal Art Society, May 2013

Notes

- William H. Whyte, City: Rediscovering the Center (New York: Anchor, 1988), 194.

- Carroll Meeks, The Railroad Station: An Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1956), ix.

- Municipal Art Society of New York, “History of the Municipal Art Society of New York,” [http://mas.org/aboutmas/history] Retrieved 18 August 2013

- ibid.

- Regional Plan Association, “Who We Are,” [http://www.rpa.org/about] Retrieved 18 August 2013

- Jenny Wilson, “Amtrak Sets Ridership Record in Fiscal Year 2011”, SmartPlanet.org [http://www.smartplanet.com/blog/thinking-tech/amtrak-sets-ridership-record-in-fiscal-year-2011/8956] Retrieved 27 November 2011

- Benjamin Kabak, “Link: The easier way to fix Penn Station ops,” Second Avenue Sagas, 23 August 2013. [http://secondavenuesagas.com/2013/08/23/link-the-easier-way-to-fix-penn-station-ops] Retrieved 15 March 2014